and the musician Thomas Witte

Richard is back. And not just any old one. This is Lars Eidinger’s Richard, which shot to legendary fame at the 2015 Avignon Festival. For his fifth Shakespeare, Thomas Ostermeier turned once again to this outstanding performer. A lesser performer would not be up to the task, for the sinister Duke of Gloucester’s powers of seduction are paradoxical to say the least. With his misshapen body and devilish mind, why does this monster continue to fascinate audiences four hundred years later? And how would he succeed in doing so without the presence of such an exceptional actor?

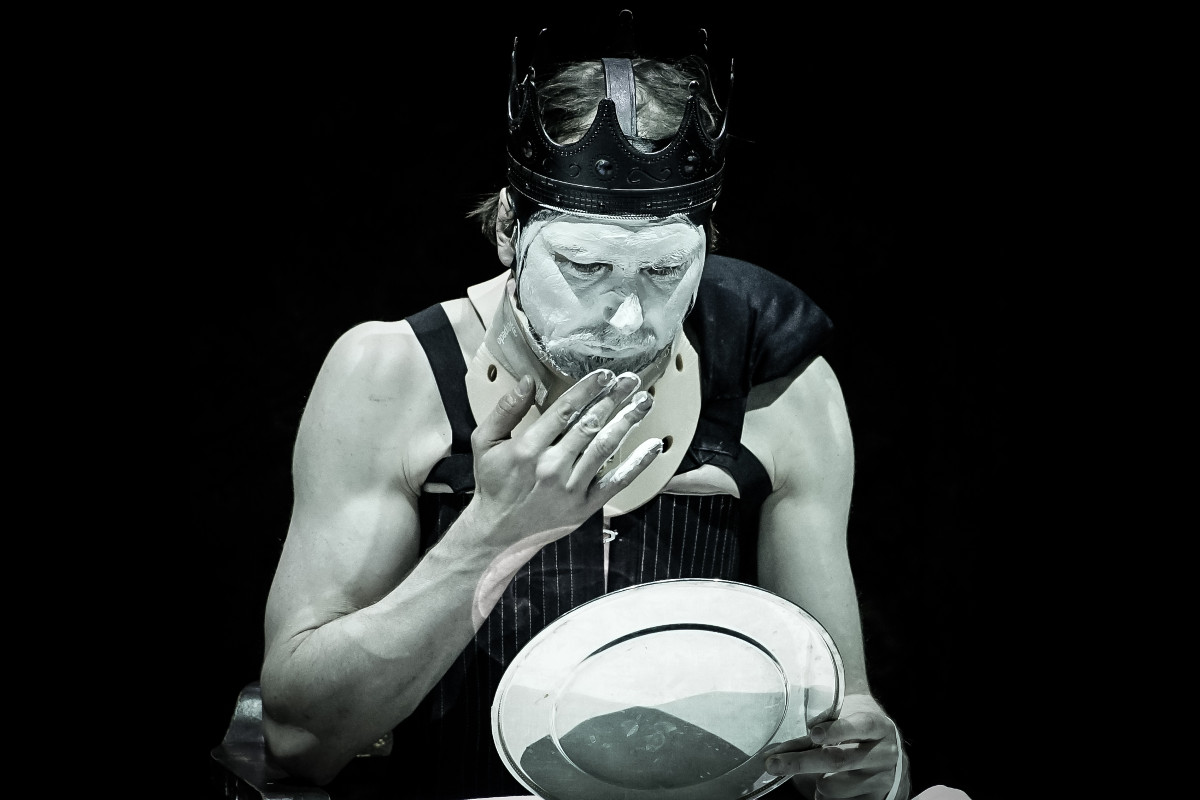

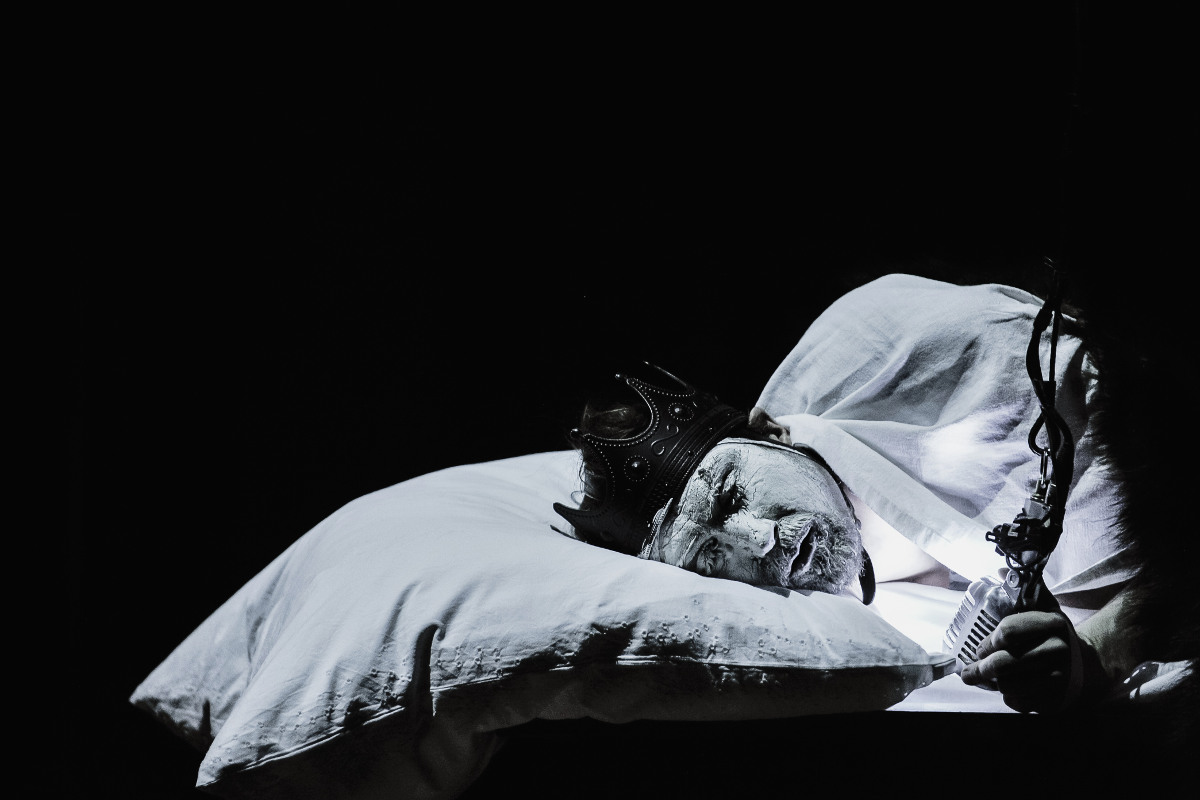

Richard, Duke of Gloucester, is the first true master of the art of putting oneself onstage that the world of theatre has ever produced. Or you could say that he is the first modern character to bring himself, theatrically, into the world. Aside from being king, he is first and foremost a spellbinding actor and gifted script writer, blessed with razor-sharp instincts and a calculating, Machiavellian intelligence. Richard is convinced that the pastimes other men can enjoy have been denied him since birth. With nothing to lose, he decides to play upon what he is. He who is lower than the lowest, animal-like, sets his mind on hoisting himself above all others, atop a mound of dead bodies, and wants to be remembered accordingly: by being no more than a succession of masks, which he juggles with consummate ease, shifting from the fury of a rock musician to the melancholy of one who remembers once being Hamlet.

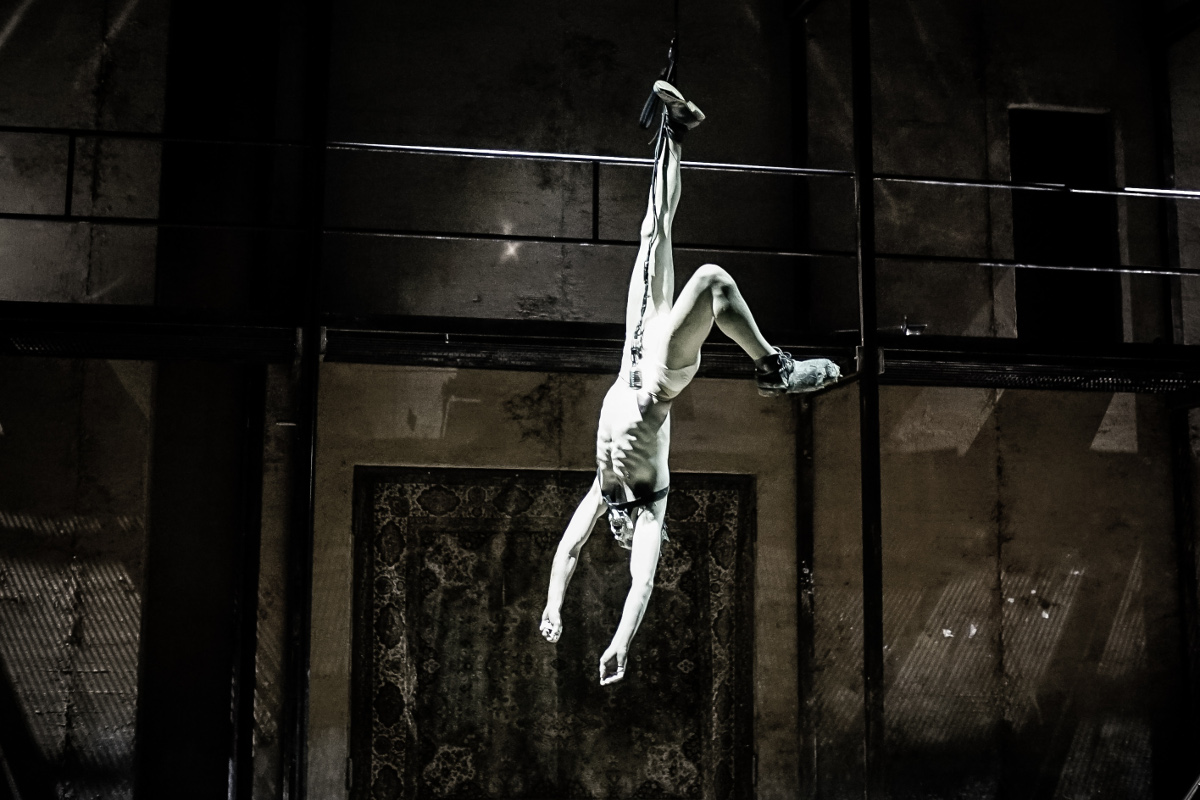

Richard’s identity, if he has one, is a matter of prosthetics: spider silks for hanging things on, cameras, microphones and the like. Perhaps the crown itself is just one more prosthesis. By calling upon us as witness, Richard constructs this vampire identity in front of us, among us even, resembling a sort of blood-thirsty machine. In doing this, he who refuses to see himself in a mirror ends up becoming, to a certain extent, our own mirror image. A deformed one, yes, similar to those in our dreams. Certain desires sometimes rear their heads in our dreams, but we are unable to stare them in the face without first deforming them in some way. But are they as unrecognizable as all that? Ostermeier’s Richard, embodied by Eidinger, asks us just that: “Have you ever wanted to do what Richard does? Have you never felt the desire to commit wrongful acts?” Such as staring at a brother’s naked, twitching body as the blood empties from its veins onto a sand-covered dungeon floor? Or handle two young children as if they were puppets to play around around with, before smashing them into smithereens? We cry out in indignation in the face of such acts, which “social and moral constraints prevent us, fortunately, from doing”, the director quickly points out. But Shakespeare’s art is such that he renders these acts not unthinkable, and makes us feel for ourselves the steeply-sliding slope that leads down to the depths of oblivion. How can we even begin to understand the disturbing powers of seduction that evil can play upon us if we do not go and see for ourselves - and within ourselves, in order to build ourselves up more strongly and understand ourselves, thanks to the omnipotent collective prosthesis that theatre itself is? We find ourselves, concludes the Schaubühne’s director, “in a free space where catharsis is possible, in which we are at liberty to play out our darkest instincts in order, perhaps, to purify and free ourselves from them”.

Cast

German Translation Marius von Mayenburg

scenography Jan Pappelbaum

dramaturgy Florian Borchmeyer

music Nils Ostendorf

lights Erich Schneider

video Sébastien Dupouey

costumes Florence von Gerkan

costumes collaboration Ralf Tristan Scezsny

production Schaubühne – Berlin

,