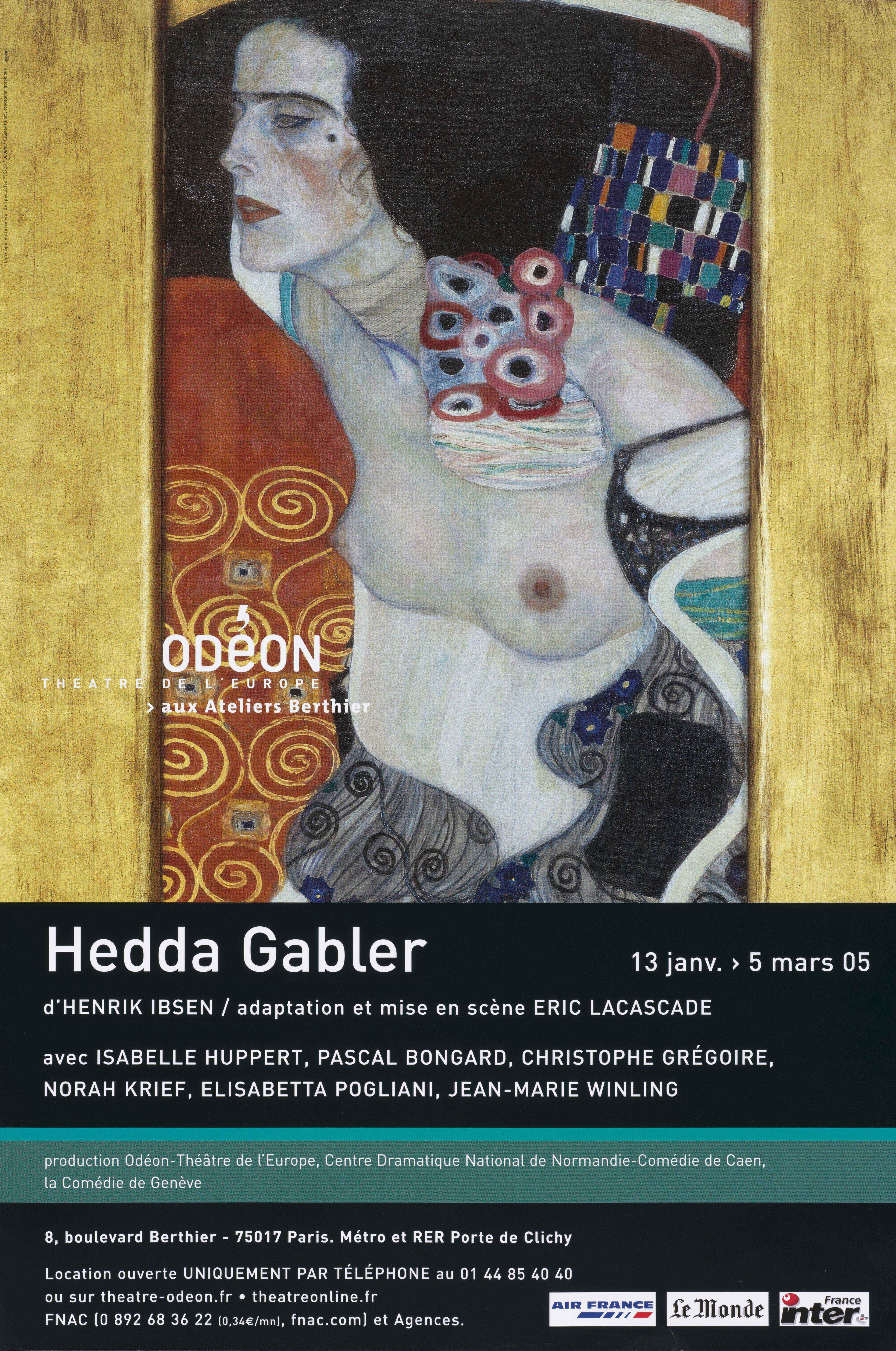

Flame and steel theater. With this play, Ibsen made a decisive contribution to the foundation of modern theater. He created a female role that stands among the most accomplished and deeply theatrical parts of the dramatic repertoire. Ibsen's portrayal of Hedda isn't the summary of a finished survey, but on the contrary, the first step of an investigation that can only end up on stage. The structure of this masterpiece is as precise and relentlessly laid-out as a battle plan. The direct and almost brutal exposition gets right to the essential points: returning from a honeymoon that lasted several months, a young couple arrives in the splendid villa that will be their home. The villa has been sumptuously decorated and finished to be fit for General Gabler's daughter.

The honeymoon lasted so long because the husband, Jorgen Tesman, led them from one European library to another so he could continue important research leading to tenured professorship. And this post is of utmost importance to him; without it, there will be no way to pay the massive debts sustained in financing the luxurious villa. Added to this inexorable rising action from the happy facade of bourgeois life to the harsh reality of their social situation, is the unfolding background charged with unspoken thoughts and feelings, threats and worries. How did Hedda Tesman adapt to the confusion of this study trip / honeymoon? How could she tolerate it? How did she spend all those days alone in foreign countries? And when she refuses to answer Jorgen's old aunt who wants to know if the family is going to be adding a new member soon, why does she do it with such brusqueness and bitterness? Each bit of information is coupled with a new question that leads the viewer further into the enigmatic depths that seem to hint at certain clues hidden beneath cold conventions, jolted moments in overly repressed lives, unquenchable pride, demands that return their intensity against oneself rather than accept the slightest compromise with the world's mediocrity. And these enigmas, these clues, orbit around a poisonous center that holds the characters, the audience and undoubtedly the author himself under its obscure fascination: Who is Hedda? What does she want? Where does her intoxicating need for destruction come from, this need to "have power over a human destiny"? And where will it lead her?

From Electra to Phedre, passing through The Three Sisters and soon Penthesilea, Eric Lacascade has long been drawn to the nuances of unrest, scandal and danger that expose major feminine figures on stage. For her part, Isabelle Huppert wanted to work with Lacascade since seeing The Seagulls in Avignon. For the past three years, the director of the National Dramatic Center in Normandy has been contemplating a common project, sometimes considering a performance with Huppert alone on stage, sometimes of a play built around a character she would interpret. One day, he re-read the story of General Gabler's daughter, Emma Bovary's distant cousin, returning from abroad to repress what life remained in her in a villa-tomb. Should she be called Hedda Tesman? Everything in her silently screams against using this name, being a wife and maybe soon a mother... So many destinies not of her choosing boring her, hindering her, strangling her. So, is it Hedda Gabler? That is the name other men call her when with her in private moments. That is, if private is what you can call moments when her husband is absent. And adultery, in its triviality, is it too ordinary, too predictable of a destiny, an overly fixed figure? Lacascade rediscovers cruelly alienated life, this woman's burning frustration. It seemed obvious to him that this was the play he was looking for. This Hedda, immobile in the middle of her small world, caught in her sterile solitude, was a role destined for Isabelle Huppert. After her memorable performance as Medea, the great actress will return to the Odeon Theater. She will again incarnate the mortifying energy of desires that tear each other, so that at least they feel themselves bleed, but in a register of strangeness that is much closer to our banal lives than a Greek tragedy.

Cast

by HENRIK IBSEN

adaptation and direction: ERIC LACASCADE

scenography : Philippe Marioge

lighting : Philippe Berthomé

costumes : Laurence Bruley

with Isabelle Huppert, Pascal Bongard, Christophe Grégoire, Norah Krief, Elisabetta Pogliani, Jean-Marie Winling

production : Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe, Centre Dramatique National de Normandie - Comédie de Caen, la Comédie de Genève

,