Since 1983, performances by the Théâtre du Radeau could make one think of Kantor, Robert Wilson, or "a Beckett who really lost his words," as Françoise Collin puts it. There are even occasional echoes of Büchner, Kafka and Hölderlin (to these last two names we can also join, as the program of this performance indicates, "the voices of Dante Alighieri, Antonin Artaud, Jean-Sébastien Bach, John Cage, Friederich Cerha, Pascal Dusapin, Carlo Emilio Gadda, Georg Friedrich Haendel, György Kurtàg, Lucrèce, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono, Krzysztof Penderecki, Luigi Pirandello, Wolfgang Rihm, Erwin Schulhoff, Giuseppe Verdi.") But with time, and despite the growing chorus of "voices" of poets and musicians assembled on the same space of theatrical immanence, it becomes more and more obvious that this theater resembles nothing other than itself. It doesn't try to say or show. It is wary of images, too quickly and easily produced (too similar to the period which nourishes itself with them, a period thrown into a panic by speed which invents new machines to go even faster). It refuses to be "necessarily the balcony of literature." It doesn't attempt to show "points of views of things," because this point of view mingles with the show itself, which "exists like an action." It doesn't draw on visible symbols that point to an invisible meaning: in Tanguy's words, "what we see isn't the code of what we don't see, what is to be seen is exactly what we see, what we can see." For this theater, "ideas are there along with things," and if there is a dividing line (rather than a separation), it doesn't divide the sign from the meaning, but rather lies somewhere in the floating interval that the theater establishes and opens like a makeshift shelter in the rumor of time, "in these two worlds divided by the stage."

Like in music, you can't express what is felt. Tanguy often borrows musical titles such as Chant du Bouc (Goat Song), Choral, Orphéon (fanfare), and today Coda (this title, writes Tanguy, "comes from the musical figure for taking up a motif at the end of a composition, extended here to theatrical movement: welcoming, gathering, renewing, unbinding"). This theater, "insomniac or carnival," ripens at its own pace, creates and repeats throughout, doesn't hesitate to interrupt itself when the state of the world demands it, isn't afraid of sometimes making you wait a long time: three years separate Coda from Cantates, which the Odeon hosted in 2001 in the Tuileries Garden. Because, as François Tanguy says, "theater is not something to talk about, it's something to do. And when you're on stage, you're right where you should be." "Before" the show, there is the patient work of immersion in the sensitive interlacing and the textures of materials, presences, sometimes words. "After" the show remains the wake of what has been shown, far from the story, "action" rather than performance. And during the show, theater is born. It "is born from a misunderstanding that it tries to extricate itself from, which it cultivates to become theater." A misunderstanding that is clearly given by the word, "representation": because this theater doesn't re-present, recapture or replace anything, not even proceeding from allusion, not having the pretension of referring to the world. Its objective is rather to clean the way we look, to direct it back to the threshold of its own enigma. As Tanguy puts it, "it will never consist of creating, through words (or theatrical material), a reality to which we would try to restore verisimilitude." Each of Radeau's projects refers the viewer to his own "theater," to "a place from which we see." Taking its sweet time, it reaches our time by the most secretive ways, continuing a work of exemplary standards, clearly and patiently contemporary, for more than twenty years.

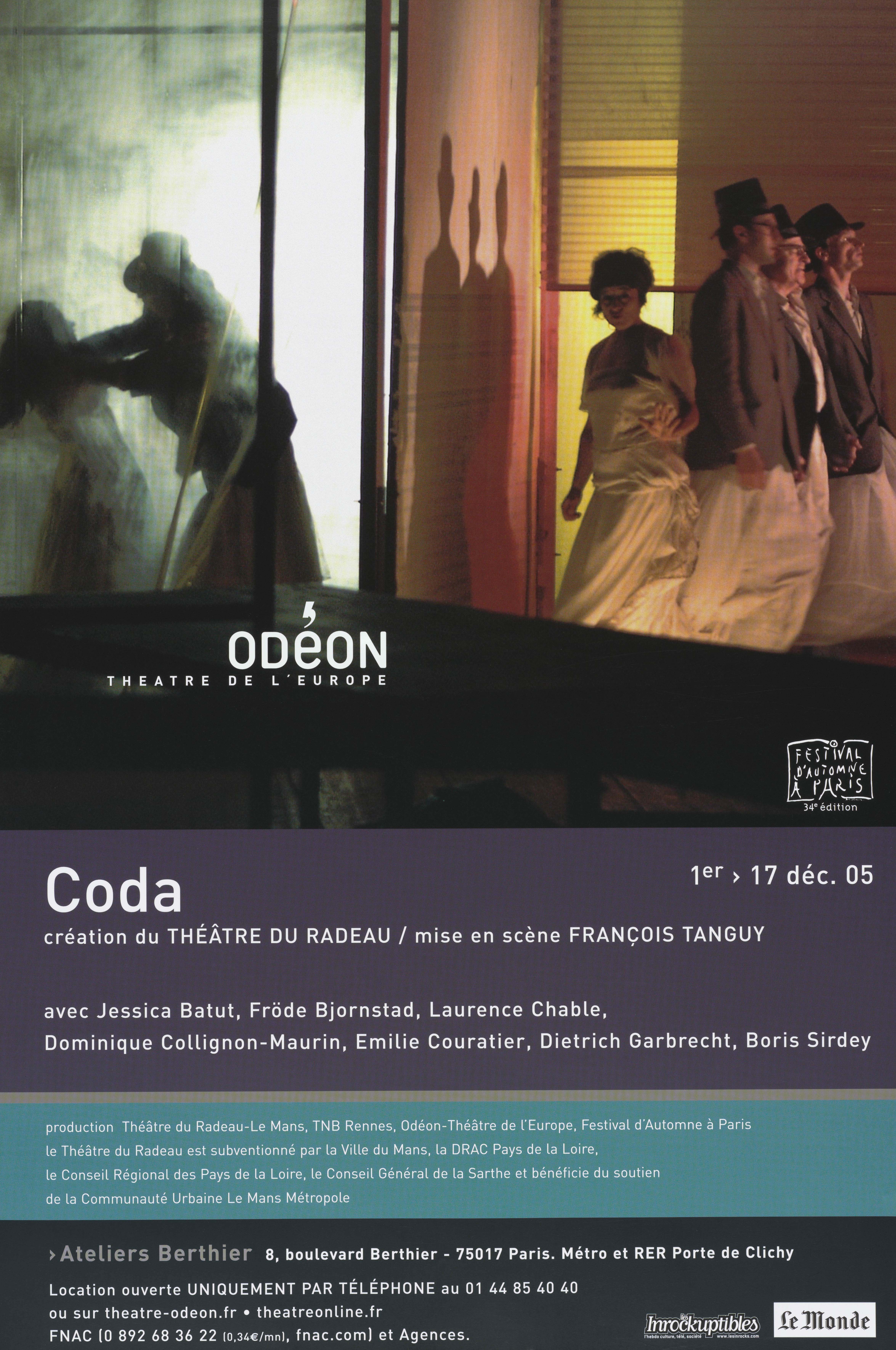

Cast

a creation of the THÉÂTRE DU RADEAU

direction and scenography FRANÇOIS TANGUY

lightings : François Tanguy

sound : Mathieu Oriol, François Tanguy

construction of the set : Bertrand Killy, Fabienne Killy, Fröde Bjornstad, Jérôme Gendron, David Frenehard, les Baltringos

with Jessica Batut, Fröde Bjornstad, Laurence Chable, Dominique Collignon-Maurin, Emilie Couratier, Dietrich Garbrecht, Boris Sirdey

and the voices of Dante Alighieri, Antonin Artaud, Jean Sébastien Bach, John Cage, Friederich Cerha, Pascal Dusapin, Carlo Emilio Gadda, Georg Friedrich Haendel, Friedrich Hölderlin, Franz Kafka, György Kurtag, Lucrèce, Bruno Maderna, Luigi Nono, Krzysztof Penderecki, Luigi Pirandello, Wolfgang Rihm, Erwin Schulhoff, Giuseppe Verdi

production : Théâtre du Radeau-Le Mans, TNB Rennes, Odéon-Théâtre de l'Europe, Festival d'Automne à Paris

le Théâtre du Radeau est subventionné par la Ville du Mans, la DRAC Pays de la Loire, le Conseil Régional des Pays de la Loire, le Conseil Général de la Sarthe et bénéficie du soutien de la Communauté Urbaine Le Mans Métropole

Duration : 1 hour

,