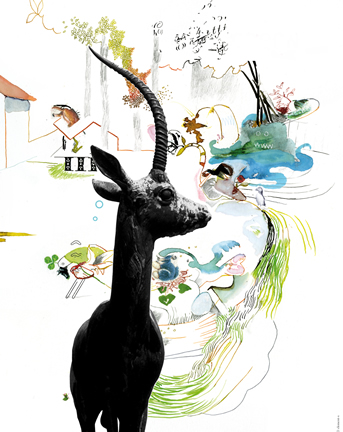

The Girl Without Hands

The Water of Life

The True Bride (original creation)

The next evening, she took out the dress embroidered with the silver moons...

Grimm

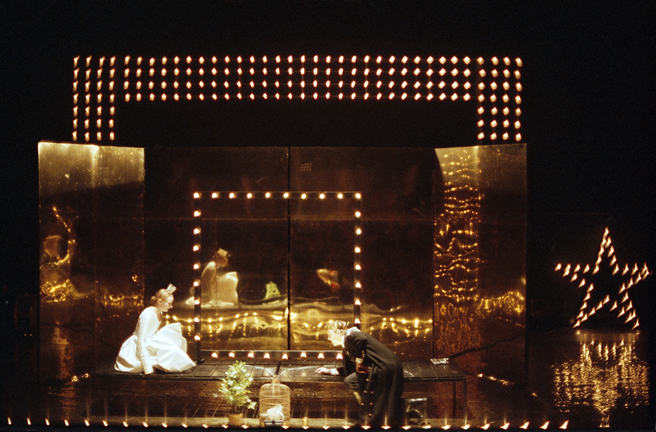

The new director of the Odéon had announced it: during his tenure as director each season would include a project that was especially accessible to the young audience. En 2007-2008 it was the original creation of Joël Pommerat's magnificent Pinocchio; this time around it's Olivier Py's turn to offer to children and their entire family three theatrical excursions into the country of legends during the holiday season. For Py the Grimm Brothers' fairy tales had for far too long "been considered as an idyllic showcase for little girls looking for Prince Charming." But most of these fairy tales have nothing childlike about them: quite the contrary. Collected and written down by contemporaries of the great generation of German romanticism their supernatural quality is all the more striking that it emerges from a background of the utmost gravity. The work of the Brothers Grimm offers "a way to speak to children about things that are not spoken about to them." Py has long appreciated the tales' false naivety and their liveliness without frills or fanciful language, qualities that in his opinion call to mind some of Shakespeare's plots. Thus it is that The Girl Without Hands (where a father, in order to escape from dire poverty, foolishly concludes a pact with a stranger who turns out to be the devil, and to whom he finds himself obliged to hand over his own daughter) can be read, in his view, as a sort of folktale version of Lear, while The Water of Life (where three sons, under orders from their sick father, set out on a quest for the sole cure for his illness) brought to Olivier Py certain faint echoes of Titus Andronicus; that is, that the cruelty that exists in the world is never far off in these lands peopled with poor orphans or families suffering from famine, where innocence is so often scorned, and childhood exploited, persecuted, indeed tortured. But Py never forgets that when faced with an audience of children "It is unthinkable to imagine anything else than to communicate a sense of hope." These tales are hard, harsh, no doubt, and the show does reflect this; but this harshness takes its young audience seriously. And this audience is triply pleased and rewarded by these Tales. First, from the pure fantasy of the story; Py, making extensive use of circus costumes and little songs, clearly has the time of his life making this fantasy vivid. Second, from the happy end which makes each adventure end on a note of hope. And last from the sheer pleasure that comes from being treated "like a grownup." Two of these tales have already been adapted by the director. On the occasion of their production at the Ateliers Berthier, he decided to add to the two, as a Christmas present to all publics, the adaptation of a third story, The True Sweetheart (or The True Bride), an astonishing junction where Cinderella runs into Donkeyskin: "Once upon a time there was a girl who was young and beautiful, but her mother had died when she was a child and her stepmother did all she could to make the girl's life wretched..."

Cast

from the GRIMM Brothers

adaptation and directed by OLIVIER PY

shows for everyone, from age 7 up

Set design, costumes and make-up : Pierre-André Weitz

Lights : Olivier Py avec Bertrand Killy

Music : Stéphane Leach

with Céline Chéenne, Samuel Churin, Sylvie Magand, Thomas Matalou, Antoine Philippot, Benjamin Ritter

La Jeune Fille, le diable et le moulin

créé le 31 janvier 2006

production CDN/Orléans-Loiret-Centre, La comète – Scène nationale de Châlons-en-Champagne

production déléguée Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe

L’Eau de la vie

créé le 31 janvier 2006

production CDN/Orléans-Loiret-Centre, La comète – Scène nationale de Châlons-en-Champagne

production déléguée Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe

La Vraie Fiancée

production Odéon-Théâtre de l’Europe

,