Je veux qu’on me distingue ; et pour trancher net,

L’ami du genre humain n’est point du tout mon fait.

Molière

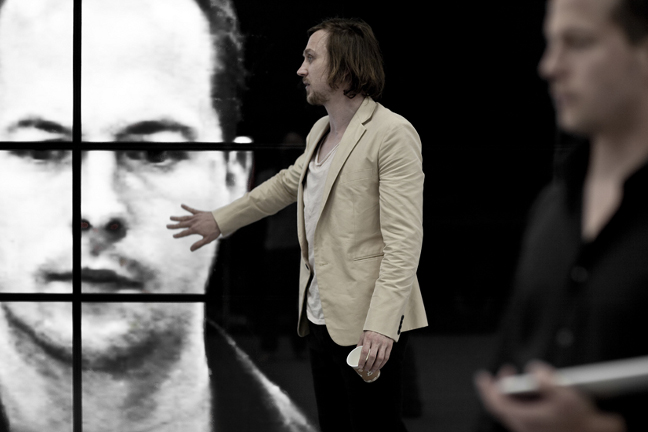

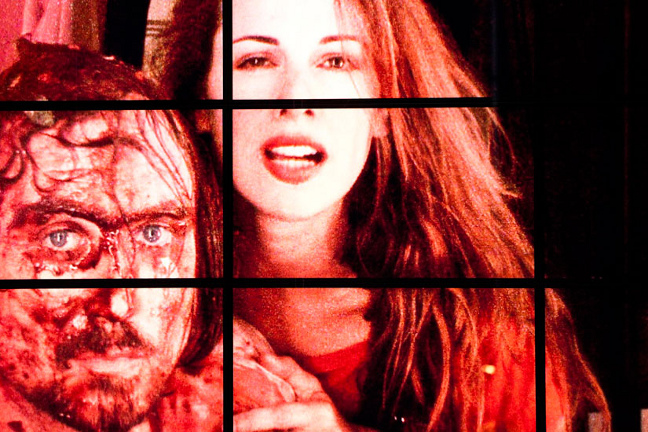

In this explosive and exploded reworking of Molière - which was the talk of Berlin when it was staged last season of the Schaubühne - Alceste is a kamikaze, a militant partisan of sincerity at all costs, who, in order to denounce the hypocrisy of social conventions, decides to personify them and take them to obscene extremes … Lars Eidenger (whose performance in Dämonen is still fresh in our minds) is totally uncompromising: after a first act full of transparent dividing walls, screens and trendy gadgets, which seems to establish a cold and clinical mise-en-scène (Oronte reads his sonnet from an iPad !), in the middle of Act 2 Aleste literally smashes up this décor for chic beautiful people. He lays on a table and covers himself in sauce, drops his trousers, and empties dustbins on the stage, which he transforms into a rubbish tip… In France although we are fortunate to be able to experience these masterpieces in Molière’s French, our desire to remain faithful to the original text can preclude new, more imaginative approaches to the plays. We rarely have the opportunity to see a Molière who returns from strange lands to which he has acclimatised. All the more reason, then, to pay tribute to Ivo van Hove’s Misanthrope, a worthy successor to his Roman Tragedies, which made a big splash at the 2008 Avignon Festival. The play bursts with trashy energy, and is dominated by the righteous anger of an unstoppable Alceste. Is he a sick man, afflicted with an overactive spleen? If that is the case, his speeches can be taken as an expression of his melancholy, allowing his friend and confidant, Philinte, to be given the role of showing the “middle way” for us to take when in society. But is Alceste’s critique of humanity really no more than a symptom of an individual malaise? Leaving aside his tendency to exaggerate, his critique is not completely unfounded. Influence peddling, backscratching and dishonest games of seduction are commonplace in a society where fraudulent behaviour is the norm. Everyone seems to accept this state of affairs, and allows themselves to be corrupted. Philinte, with his “middle way” appears just as compromised as the rest. Alceste is at the end of his tether – he is determined to tell the truth, even at the price of becoming a laughing stock and a scapegoat. But does not his acting out make him appear to be unbalanced and self-destructive, and hence deserving of social exclusion? Ivo van Hove confronts us with the following questions: what value is a truth which involves a violent gesture of isolated revolt – and, on the other hand, what of a society which does not allow such a gesture of revolt to be expressed?

Cast

in German, with overhead French titles

by Molière

directed by Ivo Van Hove

March 27th – April 1st, 2012

Ateliers Berthier / 17e

Translation : Hans Weigel

Dramaturgy : Maja Zade

Scenography & lights : Jan Verseweyveld

Costumes : An d'Huys

Musique : Daniel Freitag

Video : Tal Yarden

With Lea Draeger, Lars Eidinger, Franz Hartwig, Corinna Kirchhoff, Judith Rosmair, David Ruland, Sebastian Schwarz, Nico Selbach

production Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz – Berlin

Created on September 19th, 2010 at the Schaubühne am Lehniner Platz – Berlin

First time in France

,