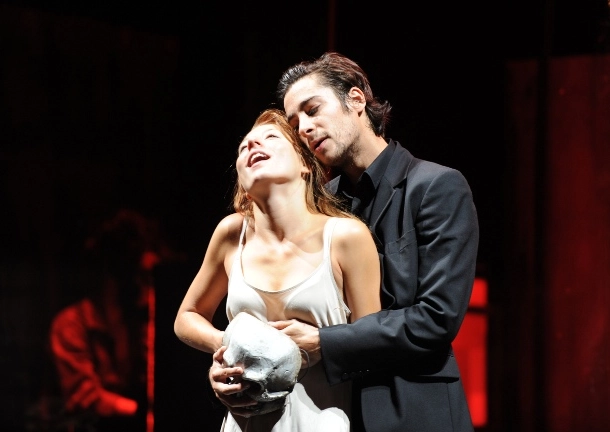

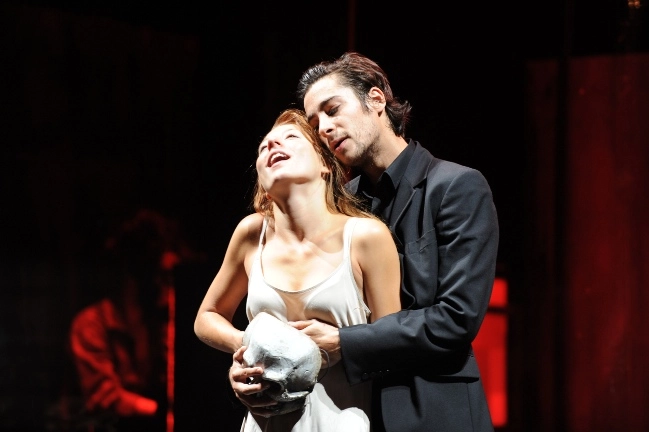

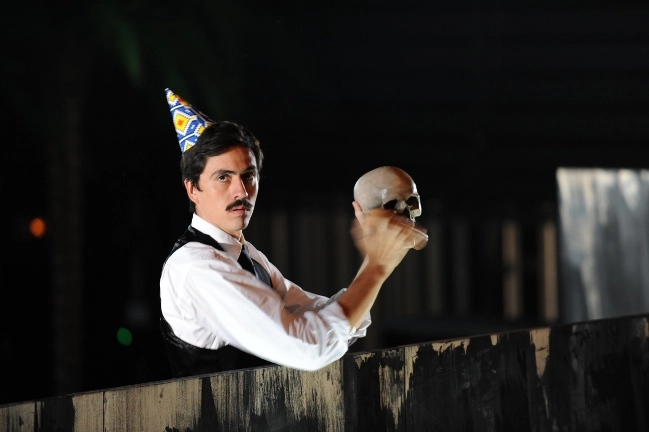

Romeo and Juliet

September 21 2011 to October 29 2011

A lightning before death…

Shakespeare

What a curious play, so famous and yet, so little known ! The last performance of Romeo and Juliet at the Odeon Theater harks back to 1971. And in fact, since the beginning of the 19th century, the average interval between two « new » productions of the play, has been about 40 years. How does one explain the enormous discrepancy between a work’s reputation, one that counts amongst the pillars of Shakespeare’s repertoire, and its rarity on our stage? One of the reasons undoubtedly, has to do with purely material concerns: the great drama about the lovers from Verona demands a large cast, a multitude of extras, sophisticated stage sets, a lavish party in the very first act. But we could say the same thing about other Shakespeare plays. There must be other reasons: between the playwright and the audience’s gaze, romanticism and opera have slipped in, and they are perhaps responsible for imposing upon our collective consciousness, a simplistic and kitsch cliché, which has turned Romeo and Juliet into a simple melodramatic news item, a beautiful and sad yet somewhat superficial love story, transformed through the grace of the magician’s language. Olivier Py came to Shakespeare without any preconceived ideas. And since he recently staged Gounod’s Romeo and Juliet, directed by Marc Minkowski in Holland, he has returned to the original text in order to flush out something else than what the opera seems to have retained. He had an intuition: if they are truly in love, these two sublime lovers, it is precisely because their love is impossible. It is not in spite of the world around them, society, prejudice, hostility between the two families or their own penchants that the amorous spark is lit: instead, it is because of all these obstacles. It is as if everything were torn asunder, all of the safeguards, the safety nets that make up what we call the world – and in the gaping chasm of this tearing-asunder, the dizzying freedom of the true, the real world appears, the world that our lovers set free for each other. It is this wild, inaugural freedom, much more than the fatality of a race to death that caught Olivier Py’s attention. Each of the two lovers stands as a door to infinity for the other one. “A lightning before death” (V, 3, 90): in order to convey the full emotion of the lightning speed with which these lives, so quickly devoured as they go from childhood to death in just a few days, the director has gambled on concentration and simplicity, and youth, having confided the roles of the two lovers to Matthieu Dessertine (who we already saw in Saturn’s Children) and Camille Cobbi, who he discovered during a workshop training period at the Conservatory. For his first foray into the work of a master whom he admires above all others, Olivier Py himself has toiled over a very tight and pared down version of the play, and all of the powerful and elliptical energy, the flamboyant state of urgency inherent in the grand Shakespearean language, are present for the roll call.